Art Basel, Miami Beach

Meaning depends on unmeaning. Evolution is a text like this. Just like reading a novel loaded with "too much" information, the more details we find, the more gaps we perceive. The more we know about strange strangers, the more we sense the void. Determined to think interconnectedness to the end, [this] ecological thought produces a mental openness far more disturbing than outer space.

—Timothy Morton

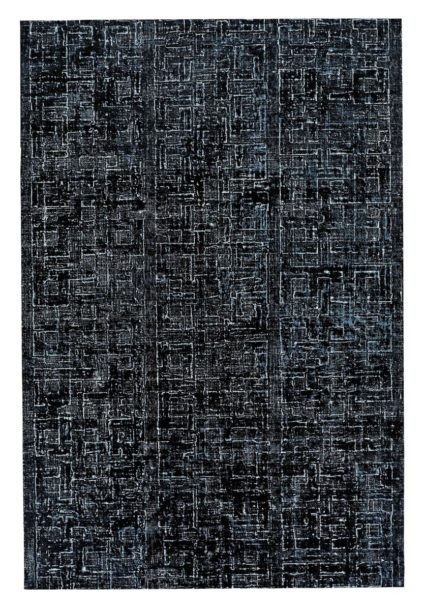

Artworks exist neither as pure material nor as pure concept. Even the most formally structured or ephemeral works emerge from the imbrication of matter and cognition. This relationship between thing and thought is the bedrock of an intricate network of relations that we might call an ecology, following philosopher Timothy Morton. The conception of an art ecology necessitates that art be thought of as more than a series of discrete objects, and rather as nodes in a massively distributed field—of exhibitions, discourse, social spheres, and that which art gestures toward without being able to directly name. Morton calls this field a “mesh”—a sprawling and intricate network of categorization and relation that denies full comprehension: “The mesh of interconnected things is vast, perhaps immeasurably so. Each entity in the mesh looks strange. Nothing exists all by itself, and so nothing is fully ‘itself.’”

This denial of a singular fixed existence or identity evokes something of the unknown, of that which is beyond empirical knowledge. Yet the unknown need not be figured in negative terms. While a lack might be apprehended as literally a void of information, it might also be figured as an open door. And that which is uncanny is often the source of revelatory art.

As the twentieth and twenty-first centuries witnessed unprecedented advances in exploration of the unknown, artists found inspiration both in the thrill of scientific breakthroughs and in the advancing frontier of outer space. They made use of the radical openness of their forms to further speculate on what might exist beyond the limits of our world and familiar cognitive territories.

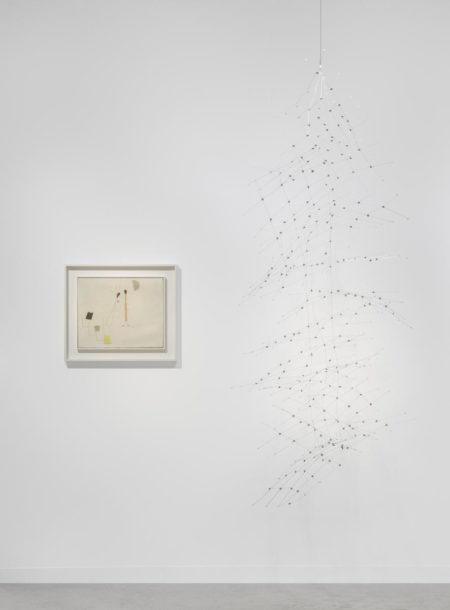

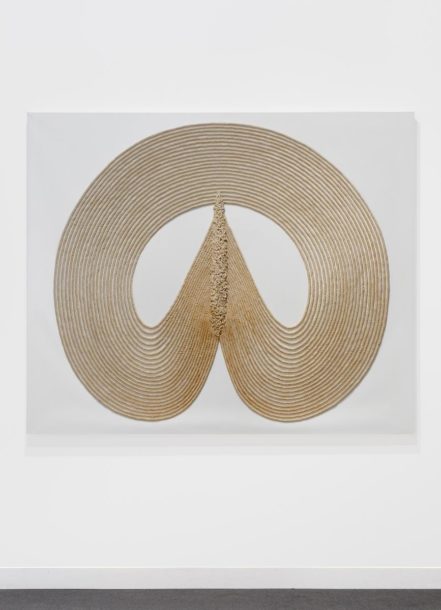

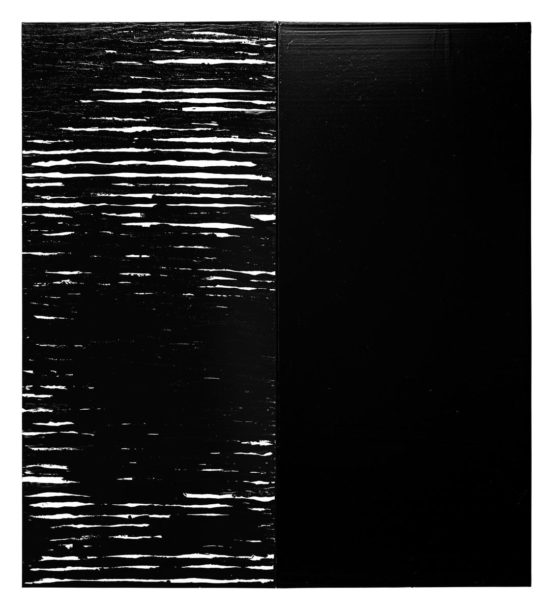

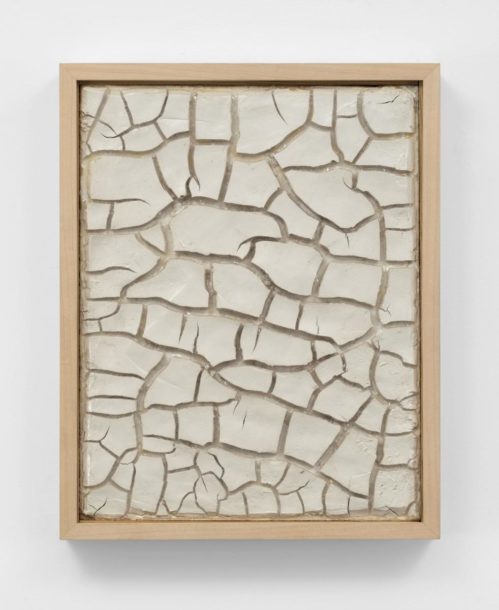

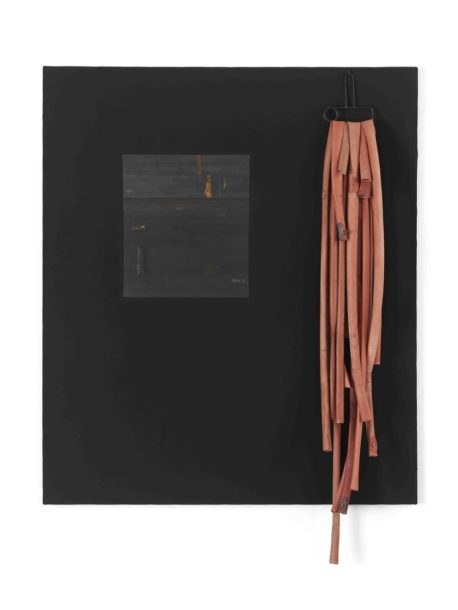

Dominique Lévy Gallery’s presentation at Art Basel Miami Beach highlights works that engage notions of the void, the unknown, and outer space. Artists' fascination with the beyond has manifested in artworks that conjure mysterious dark portals, as in Lee Bontecou's swirling eyes. For others, such as Alexander Calder, the complex movement of matter on both microscopic and interplanetary levels lends a playful formal inspiration. In the works of Lucio Fontana, Frank Stella, Joel Shapiro, and Tony Smith, sculptural forms variously connote meteorites and totemic space-age vehicles and monuments, while the canvases of Alberto Burri and Enrico Castellani resemble alien topographies. And for the iconoclast Carol Rama, compositions that incorporate everyday objects like doll eyes and bicycle tires are invested with futuristic, quasi-alien allusions.

One of the highlights of the booth is Le soleil recerclé (1966), the definitive set of painted wood reliefs by Jean Arp. Combining geometric and organic forms, and at once abstract and figurative, these pieces evoke planetary systems in motion. Indeed, two of Arp's best known series from the 1930s and 1940s were titled Constellations and Configurations and were marked by this allusion to both cosmic and biological phenomena, somewhere between clouds and cells reproducing.

For these artists and others included in Dominique Lévy’s presentation, an interconnection of formal innovation, conceptual rigor, and boundless curiosity about what exists beyond our world's limits combine to produce a powerful artistic energy. This energy, coursing with the will to encounter the unknown and the emergent, defines these singular artworks, these strange strangers.