The Friendship between Lee Bontecou and Joseph Cornell

In a postcard mailed from Mallorca to New York on August 17, 1962, and addressed to Joseph Cornell, Lee Bontecou explained her recent absence to her friend: “Dear Joseph: I guess you probably wondered what happened but I suddenly caught a chartered flight in July and have been here ever since. I went back to Rome and then Madrid. The Prado is just full of beautiful things […]” she wrote.[i]

Though their aesthetics were vastly different, artists Bontecou and Cornell were inspired by one another’s art, and for a time during the 1960s the two were good friends, despite their twenty-eight year age difference. Early in her career, Bontecou experimented with a series of boxes comprising welded frames that held walls of muslin or canvas, scorched with an acetylene torch. Inside these burnt walls, Bontecou hung miniature spheres that art writer Mona Hadler likens to “caged worlds.”[ii] Though, as Hadler describes, Bontecou’s practice would transition from these, “…small, boxed worldscapes to aggressive, large-scale constructions…,”[iii] aspects of this more Surrealist approach to artmaking would remain. In particular, her work often evokes a sense of uncanny recognition through objects rooted in recognizable imagery that nevertheless remain distinctly ‘other.’ Hadler describes Bontecou’s use of found objects as a point of intersection between her practice and the Assemblage artists who worked during the same time period, and in this way Bontecou’s work may also be linked to Cornell who, the artist would later say, “had beautiful worlds in his boxes.”[iv]

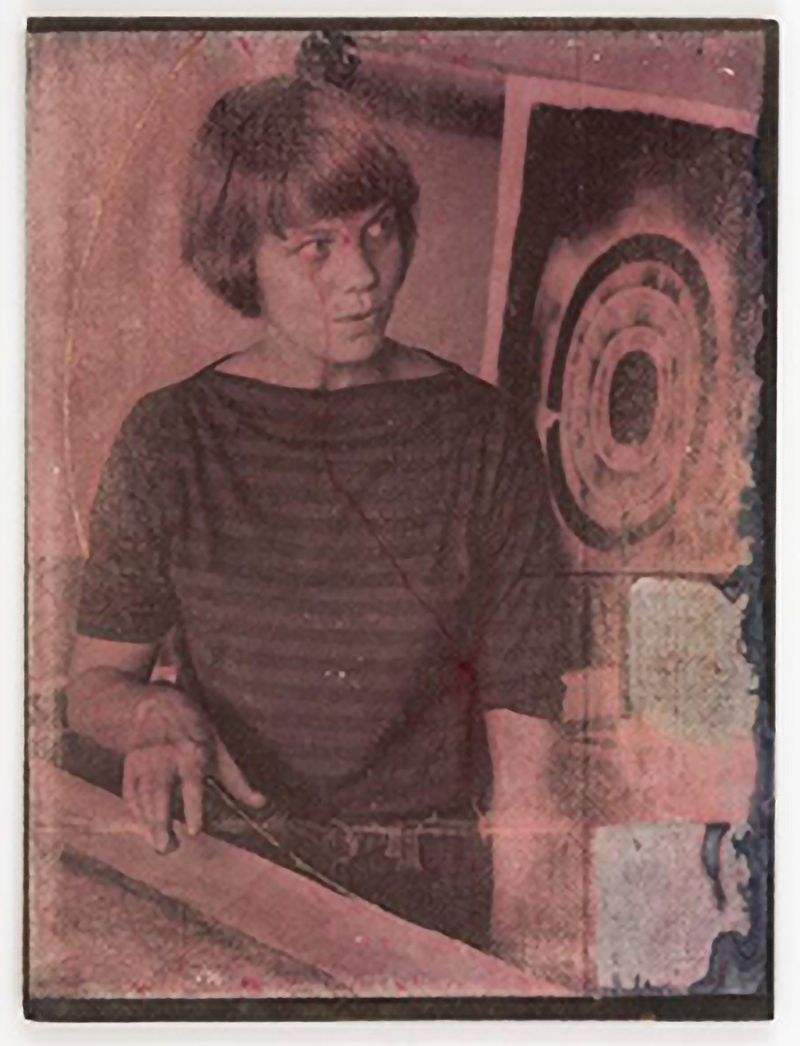

The two artists were introduced early in the 1960s by dealer Leo Castelli, [v] and as the friendship developed, Cornell’s appreciation for the young artist’s work grew. Cornell had a practice of building dossiers on individuals who interested him or whom he admired, [vi] and he built a file on Bontecou; he also incorporated her portrait into some of his collages. [vii] Kirsten Swenson, Associate Professor of Art at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, describes this file as comprising, “…observations, memories, poems, photos by Hans Namuth and clippings, which he kept in a file marked ‘L.B.’” [viii]

Bontecou’s work, some of which incorporated military equipment including gas masks and helmets, was in many ways a response to the heightened political rhetoric of the United States during the Cold War, and reflected the pervasive social anxiety of nuclear conflict, particularly around the period of the Cuban Missile Crisis. [ix] Swenson explains that Cornell saw Bontecou’s art as premonitory, foretelling a dark outcome for humanity: he described her as a “space Sybil” and a “prophetess.” [x] While the artist Donald Judd, a contemporary of Bontecou’s, related the motif of openings and voids in her work to something Swenson sums up as a “fusion of war and eroticism,” [xi] Cornell saw this recurrent feature of Bontecou’s work as something more spiritual, relating it to the Bocca della Verità, the “mouth of truth.”

Located in Rome in the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin, the Bocca della Verità is a large stone slab carved in the shape of an old man’s face, open at the mouth. Though some historians now believe that its original purpose was simply to be used as a drain cover, during the middle ages a myth developed that anyone who placed her hand in it and told a lie would have it bitten off. [xii] The stone and the story formed around it have become part of the rich landscape of Rome’s real and imagined history, and today it remains a popular tourist attraction. Bontecou saw the Bocca della Verità while in Rome, and Hadler believes she likely discussed the story with Cornell. [xiii] In a journal entry dated to February 2, 1962, Cornell wrote:

2/1/62 Bontecou “mouth” collage 10×14 new

[I]n other days there were the “mouth of truth” and the “lion’s mouth” of the Venetian Inquisitions, then, there is the terror of the yawning mouths of cannons, of volcano craters, of windows opened to receive your flight without return, and the jaws of great beasts; and now we have Lee’s warnings.” [xiv]

There is perhaps no greater indication of what these two artists’ friendship meant to each, than the fact that in a historical moment that defied understanding, Cornell and Bontecou both seem to have found an adequate response to their times in one another’s art.

This text was organized in the spirit of our exhibition Intimate Infinite, which includes multiple works by Joseph Cornell and Lee Bontecou. Intimate Infinite is on view in New York through October 24.

[i] Lee Bontecou postcard to Joseph Cornell, August 17, 1962. Joseph Cornell papers, 1804-1986, bulk 1939-1972. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[ii] Mona Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” Art Journal53, no. 4, Winter 1994, 56. Accessed via JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/777562.

[iii] Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” 56.

[iv] Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” 56.

[v] Kirsten Swenson, “’Like War Equipment. With Teeth.’ Lee Bontecou’s Steel-and-Canvas Reliefs.” American Art17, no. 3, Autumn 2003, 75. Accessed via JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1215810.

[vi] Jennifer Mundy, “An ‘overflowing, a richness & poetry’: Joseph Cornell’s Planet Set and Giuditta Pasta,” Tate Papers, no.1, Spring 2004. §4. Accessed online. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/01/an-overflowing-a-richness-and-poetry-joseph-cornells-planet-set-and-giuditta-pasta.

[vii] Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” 56.

[viii] Kirsten Swenson, “’Like War Equipment. With Teeth.’ Lee Bontecou’s Steel-and-Canvas Reliefs.” American Art17, no. 3, Autumn 2003, 75. Accessed via JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1215810.

[ix] Swenson, “’Like War Equipment. With Teeth.’ Lee Bontecou’s Steel-and-Canvas Reliefs,” 74.

[x] Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” 56.

[xi] Swenson, “’Like War Equipment. With Teeth.’ Lee Bontecou’s Steel-and-Canvas Reliefs,” 77.

[xii] Mary Beard, “The mouth of truth,” Times Literary Supplement, July 23, 2015. https://www.the-tls.co.uk/the-mouth-of-truth/.

[xiii] Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” 56.

[xiv] Joseph Cornell Papers, reel 1060, frame 632, quoted in Swenson “’Like War Equipment. With Teeth.’ Lee Bontecou’s Steel-and-Canvas Reliefs,” 76. In the note, Swenson states “It is possible that Cornell is again quoting another source here, but it seems likely that the words are his own jottings about Bontecou’s ‘warnings.’”

[xv] Hadler, “Lee Bontecou’s ‘Warnings’,” 56.

[xvi] Swenson, “’Like War Equipment. With Teeth.’ Lee Bontecou’s Steel-and-Canvas Reliefs,” 74.

More stories

Lévy Gorvy Announces Mickalene Thomas: Beyond the Pleasure Principle

New York | London | Paris | Hong KongJun 3, 2021

PALM BEACH GALLERY HOP & CARPENTER VIOLIN TRIO

Palm BeachMar 6, 2021

Donate Clothing in celebration of Pistoletto's Rebirth Day in New York

New YorkDec 21, 2020

Lévy Gorvy updates its Chinese name to

"厉蔚阁" with appointment of Rebecca Wei in Asia

Hong Kong

Dec 15, 2020

In Conversation | Dominique Lévy & Loa Haagen Pictet

Dec 5, 2020

Pierre Soulages on CBS Sunday Morning

Nov 8, 2020

Rebecca Wei Named Founding Partner of Lévy Gorvy Asia

Sep 24, 2020

LÉVY GORVY TO OPEN A PARIS GALLERY SPACE

Jul 2, 2020