How One Exhibition Helped Change the French Perception of American Art

By the early 1950s, Calder’s reputation as an artist had taken on an appropriately international profile; this, combined with his independent spirit, [i] made him a natural choice for inclusion in the exhibition 12 Modern American Painters and Sculptors.

12 Modern American Painters and Sculptors was a joint effort between the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, then under the direction of Jean Cassou, and New York’s The Museum of Modern Art, lead by Alfred H. Barr Jr. Cassou had approached Barr with the offer to create an exhibition of American painters and sculptors for France’s most prestigious institution specializing in modern art [ii]—in Cassou’s words, 12 Modern American Painters and Sculptors was to be, “a small and exciting show of dramatic contrasts.” [iii] But in the postwar era, politics was never far from view, and as Gay McDonald describes, a gesture of international cultural exchange such as this took on geopolitical significance. Ultimately, the exhibition would also play a crucial role in establishing respect for American art among the French populace. [iv]

Throughout French cultural circles, there was hostility toward the United States, and this often extended to the wave of young American artists who had moved to Paris after the war, as Jack Youngerman described in an interview with critic and gallery owner Colette Roberts. The Paris-based cultural office of the United States Information Service (USIS) was eager to defuse this anti-American sentiment, not least because, as its cultural officer Darthea Speyer put it, France’s artists, writers, professors, and students, were “constantly subjected to a barrage of Communist propaganda reiterating that America was a land of materialism and … unacquainted with culture.” [v] More than a vestige of McCarthyism, Speyer’s claim was supported by evidence: at the time, the Soviet Union was spending more money on cultural programs in France than the United States was spending on its entire overseas operations. [vi]

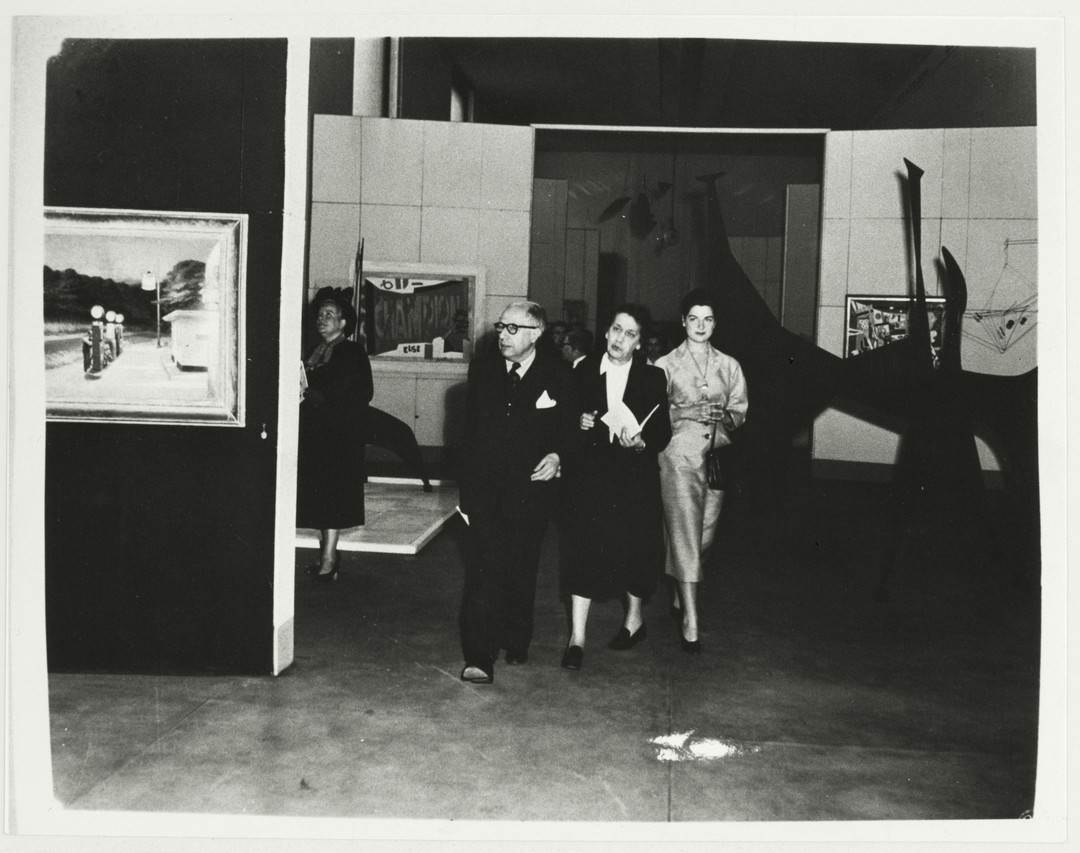

The twelve American artists included in the Musée National d’Art Moderne exhibition featured nine painters and three sculptors, all selected by The Museum of Modern Art curator Andrew Carnduff Ritchie. In keeping with Cassou’s wishes, the range of styles was broad, and included Edward Hopper, Ben Shahn, Stuart Davis, and Calder—whose works on view included the mobile Jacaranda (1949) and Black Beast (1940) (seen in the photo above, and on view now in New York in our exhibition Calder / Kelly).

The inclusion of a broad range of artists was key to the curatorial (and underlying political) argument; McDonald notes that Ritchie’s selection of artists and the essay he wrote for the attendant catalogue advanced the message that—unlike totalitarian regimes—the United States espoused no one style, and individuality was encouraged among its artists. While Calder was resolutely apolitical in his art, this curatorial statement dovetails with the strong sense of individuality Sperling described in Calder: throughout his career, he was unwilling to wear the mantle of a single artistic movement, while living and working comfortably between the United States and Europe.

[i] L. Joy Sperling, “Calder in Paris: The Circus and Surrealism,” Archives of American Art Journal 28, no. 2 (1988): 26.

[ii] Gay R. McDonald, “The Launching of American Art in Postwar France: Jean Cassou and the Musée National d’Art Moderne,” American Art 13, no. 1 (Spring 1999): 41.

[iii] McDonald, “The Launching of American Art …” 44.

[iv] McDonald, “The Launching of American Art …” 41.

[v] Speyer quoted in McDonald, “The Launching of American Art …” 42.

[vi] Speyer quoted in McDonald, “The Launching of American Art …” 43.

< Return to Renaissance and Rebuilding: Calder and Kelly’s Paris