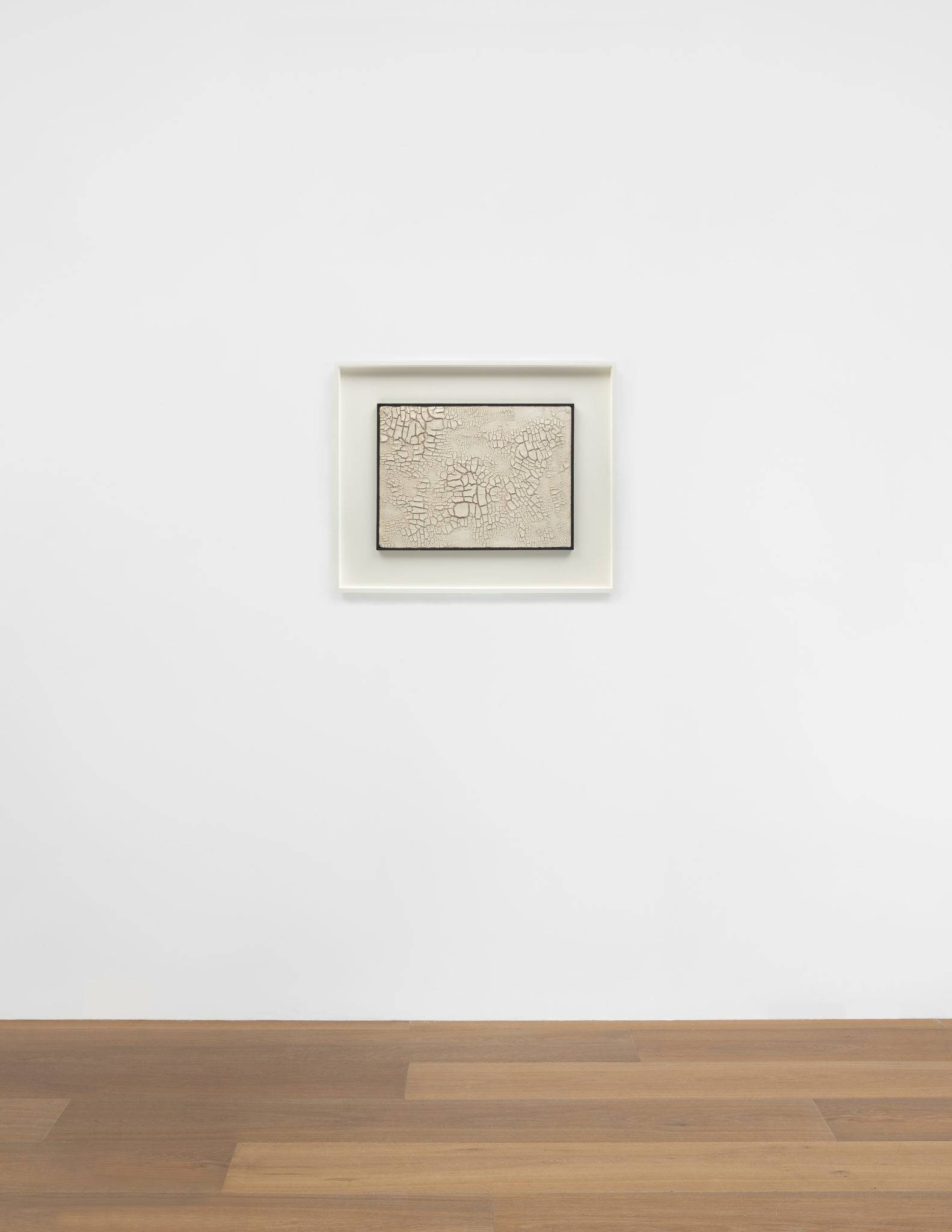

Alberto Burri

Cretto bianco (White crack), 1958

Acrovinyl on Celotex

15 1⁄8 x 20 1⁄2 inches (38.5 x 52 cm)

Signed and dated Burri 58 (on the reverse)

© 2018 / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

The nomenclature of Alberto Burri’s Cretti derives from the French term craquelure, which describes the spindly web of fissures that traverse the surfaces of aging paintings. Though craquelure is generally considered undesirable, here Burri valorizes it, using what many consider a detriment—paint’s proclivity to dry and flake—to achieve a novel aesthetic. An avid admirer of Quattrocento art, Burri conceived the aging effects observable in Old Master paintings as textured topographies, rather than self-effacing decay. Focused by the monochrome—each Cretto is a uniform shade of black or white—the series demonstrates the physicality of paint, transforming pigment from a means of illusion into a vehicle for sculptural relief.

The Cretti’s radiating crevices further express Burri’s experience of the arid landscape of the American Southwest. In the late 1950s and early 60s he developed a fascination with the mud flats of Death Valley, to which he traveled repeatedly over the ensuing three decades. Of the Valley’s parched earth, Burri observed: “The idea [for the Cretti] came from there, but then in the painting it became something else. I only wanted to demonstrate the energy of a surface” In Burri’s imagination, the Valley figured as a psycho-geography, its violent fissures furnishing an allegory for the traumas of fascist rule and industrialized warfare which indelibly shaped both his life and his art. The culmination of Burri’s cretti series occurred in 1984, when he began a land art project called the Cretto di Gibellina, also called the Grande Cretto—in the town of Gibellina, Sicily. The town was abandoned following an earthquake in 1968, with the inhabitants being rehoused in a newly built town eighteen kilometers away. Burri covered most of the old town, an area of over 1,300,000 square feet, with white concrete. The cracks between the slabs of concrete are large enough to walk between, creating a massive, labyrinthine structure in a constant reciprocal relationship with the landscape.

Curator Emily Braun locates the inception of the craquelure technique in Burri’s oeuvre as early as 1954, however, the Cretto series was largely executed between 1970 and 1979. The present work is thus a very early example of the series, and is only one of five Cretti produced in 1958, the same year that he first traveled to Death Valley. Each Cretto came into being through a delicate balance of chance and control. Using a palette knife or spatula, Burri layered a Celotex support with a mixture of kaolin, resin, zinc white pigment, and polyvinyl acetate, which cracks as it dries. Depending on the density of its application, the impasto admixture could take a week or more to settle. Over this period, Burri modeled the still pliant paint with his hands, scored it with sharp tools, and arrested its furrows with Vinavil glue. Loosely guided by the artist, the painting assumed a life of its own, enacting a temporal drama of fracture and decay through its visceral materiality. Confronted with a Cretto’s scarified surface, the viewer registers rupture as a tactile reality. Painting emerges as a vulnerable object: desiccated, scabrous, and reflective of a world that, torn apart by political repression and mass killing, could no longer be made whole.