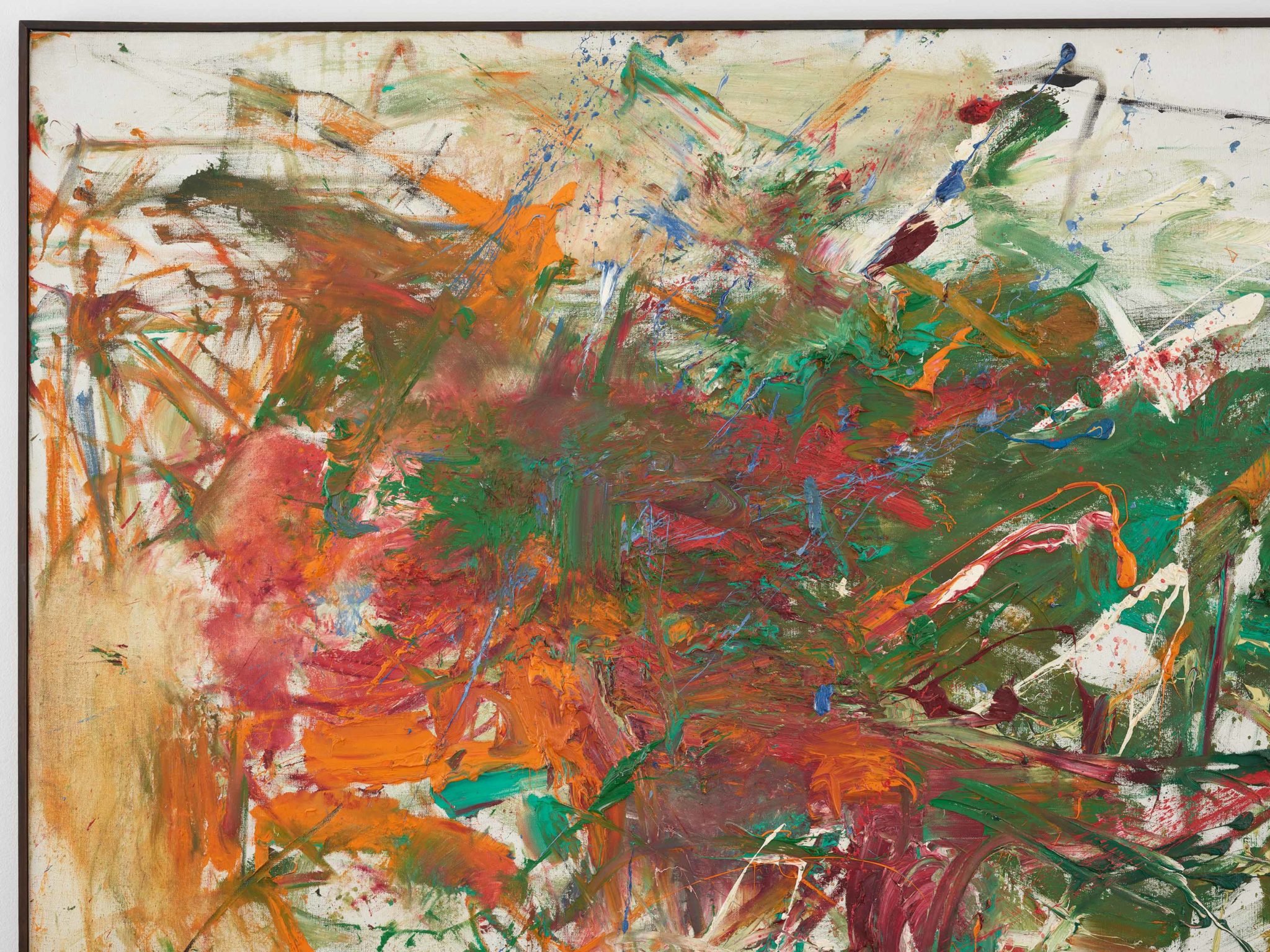

Joan Mitchell

Syrtis, 1961

Oil on canvas

51 3⁄16 x 63 3⁄4 inches (130 x 162 cm)

© Estate of Joan Mitchell

An important early work, Syrtis, 1961, exemplifies Joan Mitchell’s sustained engagement with the physicality of gesture. Its vibrant greens, reds, and oranges achieve a lush, if unconventional, beauty, revealing her intuitive sense of color. Mitchell made this painting shortly after leaving New York for Paris, where she settled in 1959 and remained until 1968 before moving to the country, an hour outside of Paris to Vétheuil.

The title of the work refers to two shallow gulfs on the northern coast of Libya, known in classical times for their dangerous quicksands. Mitchell was intimately familiar with the Mediterranean Sea, which she sailed in the summers, renting a home in Antibes with her partner, Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, and traveling to various coastal towns in his boat. Several of her other paintings from the early 1960s allude to Mediterranean locales, such as Calvi and Girolata, both made in 1964, which are named after small villages in Corsica. Like nearly all of Mitchell’s titles, Syrtis was given to the work after the painting’s completion and was based on associations that emerged once the artist observed the finished painting.

While appearing as if painted in a spontaneous surge of inspiration, Syrtis, like all of Mitchell’s paintings, was slowly and precisely composed. The result evidences what art historian Barbara Rose described as a “struggle between coherence and wild rebellion” that animates the canvas with a restless, dynamic energy. As is typical of Mitchell’s early 1960s work, Syrtis is defined by a thick tangle of marks from which isolated strokes emerge. Around its edges, large areas of canvas remain blank, tempering the density of its concentrated brushwork with a sense of atmosphere and suspension. White was an important color for Mitchell, which she associated with eternity, existential dread, and the void of non-being. In the present work, white variously underlays and overlays the central form, at once anchoring it within the canvas and interrupting its gravitational pull with discrete daubs and dashes.