Seen in Context: Agnes Martin's Gabriel

Lévy Gorvy’s current exhibition in London, FOCUS: Agnes Martin, presents the artist’s only completed film, Gabriel (1976), in conjunction with a selection of her paintings. With Martin so strongly associated with abstract painting, many are surprised to learn that, for a time, she expanded her practice to include film. As we review some of the critical perspectives on Martin’s only film, this text considers how Gabriel fits in to Martin’s practice as a whole.

***

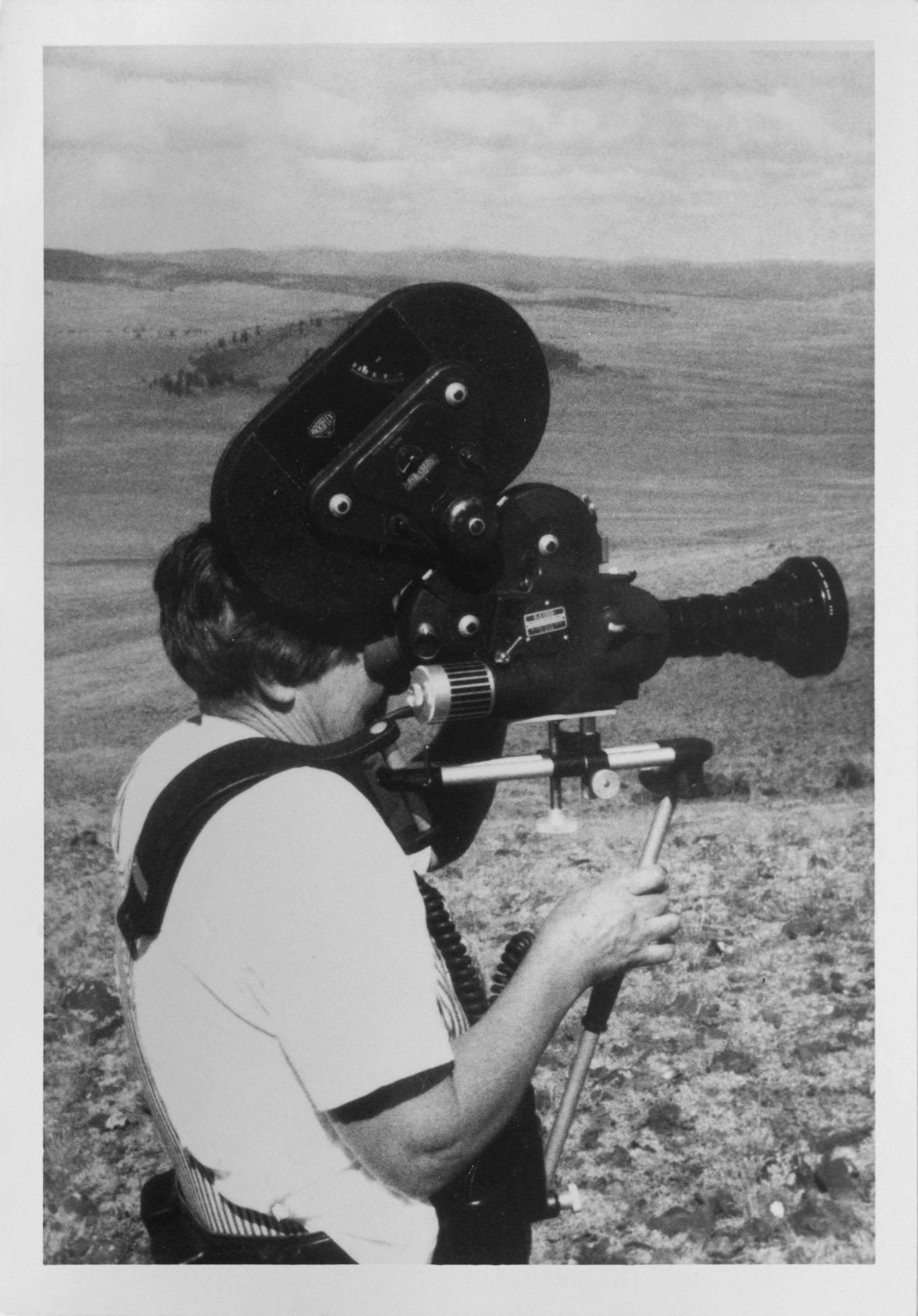

Shot using a second-hand professional camera, and made with the assistance of her friend Bill Katz, Martin’s film follows its titular character, a 10-year-old boy, as he walks through an arid yet beautiful desert landscape. Martin alternately shows us the boy as he wanders through the sun-drenched terrain and shows us what he sees. With no dialogue or ambient sound included, only intermittent segments of Bach’s Goldberg Variations break up the silence of Gabriel’s reverie. The art dealer and founder of PACE Gallery, Arne Glimcher, later wrote about the significance of the film to Martin: “To her the boy is innocence itself responding to the beauty of the natural world. The film was shot completely from his point of view. Every rock, pebble and plant struggling for survival amid their harsh environment is recorded.” [i]

Though it was not the artist’s lone filmmaking effort, Gabriel stands as her only completed cinematic work. [ii] Consequently, the question of how it should be understood in the larger context of Martin’s legacy has been a topic of debate among critics and authorities on the artist, with some, like Rosalind Krauss, dismissing the film; by contrast, Glimcher describes it as, “inextricable from the corpus of her oeuvre.”

Martin spent her early years in a Canadian prairie town, and later settled in the high desert of New Mexico—expansive, flat topographies that many, including Martin biographer Nancy Princenthal, read in the artist’s abstract paintings:

“The slow rhythms of mostly horizontal bands shift with the chromatic variations, now unmistakably responsive to the light and landscape of the high desert (vigorously though Martin would deny it).” [iii]

Indeed, Martin repeatedly denied the notion that landscape was an important theme in her paintings, [iv] yet Gabriel is a deep immersion into the light, color, and textures of the landscapes she filmed. Consequently for Krauss, who rejects the idea that landscape underpins Martin’s compositions, Gabriel is not simply an outlier, but a piece that presents an unhelpful cul de sac in the discourse around the artist:

“It is not a work Martin herself gives any indication of wanting to bracket away from the rest of her art. Yet it should be. For Gabriel constructs a reading of Martin’s own work as crypto-landscape…” [v]

As Krauss notes, there is no evidence to suggest that Martin had reservations about Gabriel—in fact, as many authorities on her art have noted, the artist consistently destroyed those artworks that she felt were unsuccessful—exactly what she did in the case of her second (and only other) film. [vi] On the contrary, there is strong reason to believe that Martin saw Gabriel as an important addition to her creative output. In 1976, while meeting with Glimcher in New York, Martin made a point of telling him where she had stored the film’s footage and negatives and asked that he work to secure a commercial release for the film in the event that something should happen to her. But while all of this supports the idea that Martin considered the piece successful, it doesn’t address the question of how it fits into her body of work as a whole.

On this point, Martin drew a straight line between the film and her paintings, saying, ”’I thought my movie was going to be about happiness, but when I saw it finished, it turned out to be about joy – the same thing my paintings are about.’” [vii]

While the artist’s observation is clearly stated, it is anything but simple. Art historian Anna C. Chave relates Martin’s discussion of her work in terms of emotional states to the artist’s interest in Taoism and Buddhism. This interest, Chave says, led Martin to, “develop an idea of art as a mode of developing awareness or heightening perception, and so as a vehicle for revelation for artist and viewers alike.” [viii]

Similarly, art historian Ruth Burgon argues that it is “misleading to understand the imagery of Martin’s film as key to its relationship with her paintings – such an approach results in a dismissal of the film as a one-dimensional appendage in an otherwise complex body of work […] it is more fruitful to compare the viewing processes they respectively offer.” [ix]

Burgon points to Martin’s use of a red filter in the first moments of the film, comparing the effect of this device to the red we see when we close our eyes against bright sunlight, and the inside of our eyelids becomes strangely illuminated. For Burgon this moment is key to the film:

“Martin’s recreation of this effect invites us, right from the outset, to view this film in a highly somatic manner. The colour renders the image anti-naturalistic, since it is bathed in red, but at the same time the device roots the image in the viewer’s body.” [x]

As the film develops, Burgon points to Martin’s use of repetition and long, extended shots focused on elements of the land, such as flowers and running water. She argues that this repetition functions to unmoor the viewer’s focus from the apparent subject matter and pulls our focus instead to the act of looking itself. [xi]

Burgon sees this phenomenon in Martin’s paintings, too, noting the visual theorist Griselda Pollock’s discussion of Martin’s grids: “For Griselda Pollock, Martin’s grids, with ‘no thing, no object, no resemblance, no motif,’ present ‘a kind of zeroing out of what accrues,’ making ‘us see seeing’…” [xii] Burgon argues that Gabriel can, in fact, help us to see Martin’s paintings more deeply: considered alongside Martin’s paintings, Gabriel “poses the question of how one might look at them as fields in flux, highlighting minute change through repetition, inviting a mode of viewing that involves not just the eyes, but the whole body as the vessel of vision.” [xiii]

That Martin was concerned with a mode of viewing rooted more in the body than in the material characteristics of what is being viewed is also suggested by a story Glimcher tells about visiting Martin with his young granddaughter, Isabelle. Martin noticed that the young girl was intently focused on a rose standing in a vase, and so she asked the girl if the rose was beautiful, and the girl replied that it was. In response, Martin proceeded to remove the rose from the vase, and concealed it behind her back. She asked the girl if the rose was still beautiful, and although she could no longer see the flower, the girl answered that it was still beautiful. Martin then declared to the girl that the beauty she was perceiving did not exist in the rose, but in her own mind. [xiv]

For Martin it seems that whether you were looking at one of her paintings, her film Gabriel, or a rose, the most interesting part was the experience it sparked within.

***

FOCUS: Agnes Martin is on view in our London gallery through April 13, 2019.

[i] Arne Glimcher, “After Completing Gabriel,”Agnes Martin Paintings, Writings, Remembrances (London and New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 2012) 88.

[ii] Nancy Princenthal, Agnes Martin: Innocence the Hard Way, Tate Talks (lecture, Tate Modern, London, UK, July 15, 2015).

[iii] Nancy Princenthal, Agnes Martin: Innocence the Hard Way, Tate Talks (lecture, Tate Modern, London, UK, July 15, 2015); Nancy Princenthal, “Lines of Thought,” Art in America, November 2015, 129.

[iv] Anna C. Chave, “Agnes Martin ‘Humility, the Beautiful Daughter…. All of Her Ways are Empty,’” in Agnes Martin, Barbara Haskell, ed. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992, 146.

[v] Rosalind Krauss quoted in Ruth Burgon, “Trips, crossings, trudges: A reappraisal of Agnes Martin’s Gabriel,”Moving Image Review & Art Journal 4, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 66.

[vi] See Glimcher, “After Completing Gabriel,” 89; Princenthal “Lines of Thought,” 126.

[vii] Arne Glimcher, “After Completing Gabriel,” Agnes Martin Paintings, Writings, Remembrances (London and New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 2012) 88.

[viii] Anna C. Chave, “Agnes Martin ‘Humility, the Beautiful Daughter…. All of Her Ways are Empty,’” in Agnes Martin, Barbara Haskell, ed. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992. Exhibition catalogue. 135.

[ix] Ruth Burgon, “Trips, crossings, trudges: A reappraisal of Agnes Martin’s Gabriel,” Moving Image Review & Art Journal 4, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 67.

[x] Ruth Burgon, “Trips, crossings, trudges: A reappraisal of Agnes Martin’s Gabriel,” Moving Image Review & Art Journal 4, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 72.

[xi] Ruth Burgon, “Trips, crossings, trudges: A reappraisal of Agnes Martin’s Gabriel,” Moving Image Review & Art Journal 4, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 73.

[xii] Ruth Burgon, “Trips, crossings, trudges: A reappraisal of Agnes Martin’s Gabriel,” Moving Image Review & Art Journal 4, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 72.

[xiii] Ruth Burgon, “Trips, crossings, trudges: A reappraisal of Agnes Martin’s Gabriel,” Moving Image Review & Art Journal 4, no. 1 & 2 (2015): 72.

[xiv] Arne Glimcher, Agnes Martin – ‘Beauty is in Your Mind,’ TateShots. Published June 5, 2015, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=902YXjchQsk.

More stories

Lévy Gorvy Announces Mickalene Thomas: Beyond the Pleasure Principle

New York | London | Paris | Hong KongJun 3, 2021

PALM BEACH GALLERY HOP & CARPENTER VIOLIN TRIO

Palm BeachMar 6, 2021

Donate Clothing in celebration of Pistoletto's Rebirth Day in New York

New YorkDec 21, 2020

Lévy Gorvy updates its Chinese name to

"厉蔚阁" with appointment of Rebecca Wei in Asia

Hong Kong

Dec 15, 2020

In Conversation | Dominique Lévy & Loa Haagen Pictet

Dec 5, 2020

Pierre Soulages on CBS Sunday Morning

Nov 8, 2020

Rebecca Wei Named Founding Partner of Lévy Gorvy Asia

Sep 24, 2020

LÉVY GORVY TO OPEN A PARIS GALLERY SPACE

Jul 2, 2020