Michelangelo Pistoletto

Rottura dello specchio–azione 2, 2017

Silkscreen on super mirror stainless steel

59 1/16 x 98 7/16 inches (150 x 260 cm)

© Michelangelo Pistoletto

The breaking of the mirror is a performance, that is, an action that takes place at a precise moment. The fragments fall to the ground, leaving holes of a different form inside each of the large mirrors. . . . These forms remain as memory, just like in a snapshot photo of the performed action. Reintegrated, then, is the same symbiosis between photography, testimony of a past moment; and the continual mutation in the flow of the present that occurs in the “mirror paintings.” Photographic memory is simply replaced by the breaking of the mirror.

—Michelangelo Pistoletto

Rottura dello specchio—azione 2 (2017) unites within a single work themes from series that are central to Michelangelo Pistoletto’s career: his self-portraiture, mirror paintings, and mirror-shattering performances. In the present work, the artist composed his own image as a figure at the forefront of the ground’s mirrored surface, integrating reflections of viewers and the exhibition space into the work. Pistoletto portrayed himself gripping the long-handled wooden mallet that he used to systematically break framed mirrors in the famous Seventeen Less One performance at the 2008 Yokohama Triennale (now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York) and in Twenty-two Less Two at the 2009 Venice Biennale. The composition of this work contrasts the stillness of the artist’s photograph, frozen in a moment of performative action, with the constant changes that occur in its reflective ground. In addition, the present work offers a profound meditation on themes of creation and destruction.

In Rottura dello specchio—azione 2, Pistoletto revisits the primary subject of his earliest mature paintings: himself. Moving from his expressionist self-portraits of the late 1950s, by 1960 Pistoletto began representing his own figure foregrounded before gleaming monochrome grounds of gold, silver, and polished, reflective black. As the artist has explained: “That was the beginning of the change from pigment to mirrors. The mirror didn’t enter my work as a found object, but through painting. In fact, it was a necessary progression after the shiny black pigments, which began to reflect like mirrors.”

These aesthetic investigations in turn led Pistoletto by 1962 to develop his foundational Quadri specchianti (Mirror Paintings), establishing the formal and conceptual concerns that he has continued to investigate through the present. He initially traced enlarged photographs of his subjects on tissue paper using the tip of a brush and affixed these life-size images to mirror-polished stainless steel. After 1971, he replaced the tissue paper with a silkscreened image, opening up new potentials for illusion and engagement. The mirror paintings incorporate the viewer and their surroundings into their pictorial space, breaking down the boundaries between the infinite and definite, such that the picture is, in the artist’s words, “penetrated by the rules of objective reality.”

The mirror’s reflection has served as a profound metaphor for mimesis, vanity, and representation in the history of Western painting from Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait (1434), to Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), to René Magritte’s The False Mirror (1929). As art theorist Soko Phay-Vakalis has noted, “Pistoletto, by pasting a silk-screened representation onto a mirror, inverts the tradition of a painting within a painting: a space is created in which the viewer co-exists with an image. The mirror captures and traps the spectators through doubling. . . . This theatralisation-by-reflection is, for the artist, a way to track down truth.”

Pistoletto’s critical reassessment of the mirror’s signifying potential is resonant with the anti-Fascist writings of his contemporaries, Italian theorists Enzo Paci, and Umberto Eco, whose 1962 text The Open Work promoted a new kind of humanism grounded in the plurality of interpretation. Moving beyond the perspectival “deep space” of nineteenth-century painting and the twentieth century’s literalization of the picture plane, Pistoletto employs the “open work,” inviting the viewer to participate in the creation of his work’s meaning rather than imposing a fixed meaning on it. He would further break down conventions of artmaking through collaborative actions that unite art and life. Reflecting on his revolutionary oeuvre, Rottura dello specchio—azione 2 commemorates Pistoletto’s performance, positioning the viewer as an active collaborator in its construction of meaning.

The dramatic gestures of shattering mirrors in Seventeen Less One and related performances actively intervene into the physical world with profound metaphysical connotations. For the artist, mirrors represent an incorruptible image of the world, offering reflections of both humans and society, and their surroundings. Breaking the mirror is equivalent to dividing the image of the universe into many fragments that can represent each individual person— fragments which, once recomposed, form society. Dramatizing Pistoletto’s performance with a compelling example of his Quadri specchianti that includes his own image, Rottura dello specchio—azione 2 commemorates this act of creative destruction, creating a work that casts new light on the meaning of that performance and on his career as a whole.

-

Andy Warhol

Ladies and Gentlemen (Wilhelmina Ross), 1975

-

Eduardo Chillida

Gure aitaren etxea, 1984

-

Carol Rama

Presagi di Birnam (Omens of Birnam), 1994

-

Mario Schifano

Untitled, 1975

-

Michelangelo Pistoletto

Rottura dello specchio–azione 2, 2017

-

Lygia Clark

Bicho em Si – Pq, 1966

-

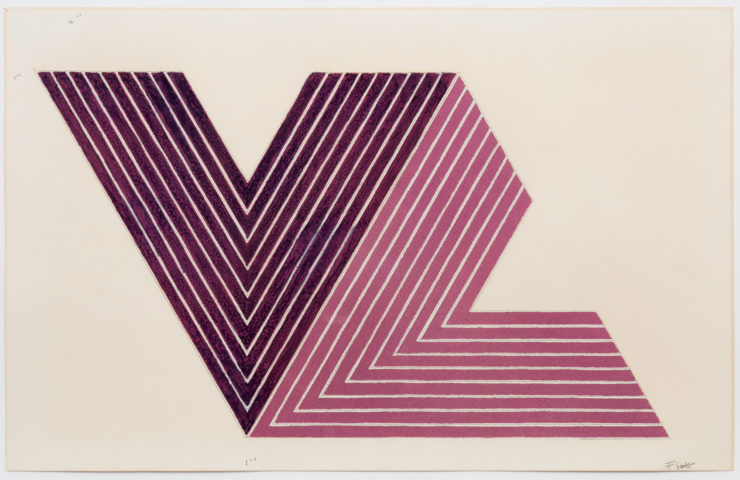

Frank Stella

Untitled, 1969

-

Enrico Castellani

Superficie argento, 2006

-

Jana Euler

Dirty Gossip Rain, 2013

-

Carol Rama

Bricolage, 1963

-

Mickelane Thomas

Sugar Baby, 2004