Artist Statement | Thoughts on My London Exhibition

Halfway through preparing for my London exhibition, COVID-19 became a global pandemic, and rages to this day. I am beside myself with shock, and what most people feel is a sense that the world has changed irrevocably, becoming far more uncertain than before—they feel a nameless terror of elites and their political intrigues. I’m no stranger to such uncertainty, but, this time, it appeared with such unconcealed ferocity that it felt like a war. A sense of upheaval sprung from these new phenomena; upheaval filled my life and surroundings. A new order rose from the old, as if new paintings were meeting old ones.

I began to think continuously about new paintings. Of course, I also thought about how tired a subject painting had become, in an age where video clips fill social media. But I do not think such a thought is necessarily futile; a medium is just a medium, and its development always contains revolutionary possibilities. What I want is the experience of communicating, of perceiving anew.

I have always believed that painting is a lonely endeavor. As Francis Bacon said, art never surpassed Egyptian times. This is also how I understand our job today: to use intuition to consciously grasp our perceptions. I believe this is the most accurate form of expression in the visual arts, and I call it “multi-dimensionalism,” though, of course, it isn’t actually a philosophy. Certain theorists ridicule today’s artists for their inability to look at the world with innocent eyes—but in so saying, they reveal why they aren’t artists themselves.

I’ve inherited my subjects—mountains, water, and landscapes—from painters from my alma mater, China Academy of Fine Arts, and from China’s ancient literati painting tradition. The landscape’s content is not, in itself, important; my work does not refer specifically to a certain place. Rather, my understanding is similar to the Chinese concept of shanshui (landscape), one in which social and psychological distance figures prominently (as demonstrated, for example, by Zaixin Hong’s explanation of the traditional Chinese notion of distance, and the foreword to Michael Sullivan’s Symbols of Eternity. After all, many painters’ lives have been bitterly difficult, historically). At the same time, I hope my paintings are open-ended, able to draw inspiration from different cultures; xenophobia and self-isolation lead to cultural and social decay.

In this exhibition, I hope to express the states of, and spatial relations between, objects and scenery. Once, during a trip, I passed through an incredibly steep cliffside (I later took Brett Gorvy and Danqing Li there to show them what I meant). To walk through these cliffs, your body has to assume a posture quite different from how you would normally walk, and consequently, I felt time slow down, while my sense of up and down, left and right lost its meaning. This acute, personal feeling taught me that spatial relations are always already subjective and individual; they can’t be reduced to mere sensory experience or fit to any one standard. This is why I have rearranged the objects in each of the paintings here, based on memories of things that happened to me and certain echoes that I can’t forget.

My work is influenced by Pablo Picasso and David Hockney. Picasso enfolds different spaces and times into the same two-dimensional surface; Hockney does something similar, but he focuses more on certain lacunae found in photographs and mechanical reproductions.

If we compare the photographic works of Hockney and Ed Ruscha, my point becomes clearer. I think both perfectly demonstrate how to fold space through a medium shot (a photographic capture at a medium distance from the subject) a principle that is found in early Chinese painting.

This scroll painting, Nymph of the Luo River (c. 345–406 CE), is similarly a medium shot; by juxtaposing different heights and sizes of people and trees, it achieves a kind of musical rhythm. I want to take these rhythms and pull them outside of the painting, towards the viewer, expressing the relationship between closeness and distance, height and shortness, on a different axis.

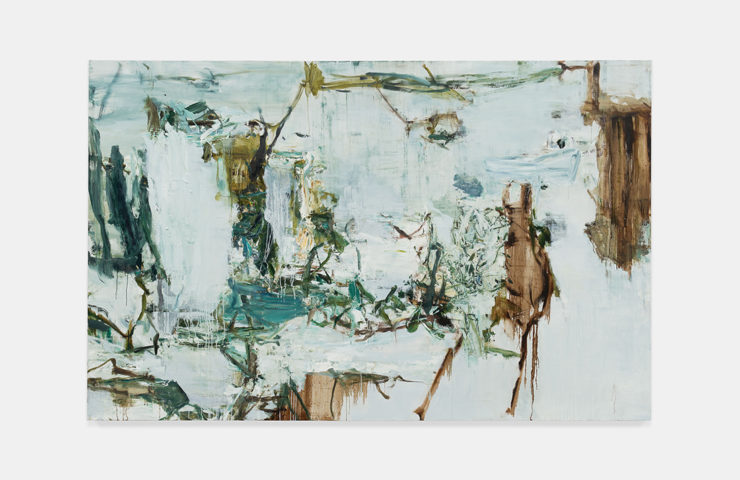

This work, Green Mountains Shall See Me Like This (2019) employs the method I’ve just mentioned, giving viewers a chance to move their gaze across the span of the composition and get a feel for the rhythm of nearness and distance. I’ve also employed the principle of three perspectives used in traditional Chinese painting, one which arranges coinciding bits of detail based on their distances. In order to make the structure of the painting as simple and clear as possible, I restrain myself to no more than two main colors.

For my representational language, I have chosen the most traditional of painterly media. I do this not out of a moral obligation to classical painting, but because I like the directness of the medium and trust in the texture and soul of painting. I do like many Abstract Expressionist artworks—they have encouraged me to express myself in a liberated, personal way. They all demonstrate a kind of honesty to the painter’s own perceptions and a feeling of urgency, as if every brushstroke is painted out of necessity.

Today’s images are much easier to compose and produce; this convenience has bred a kind of consumerist image production which foregrounds visual effect and technique. I am wary of this trend. We live today in a world that is woven out of information and images; each person has the chance to create images, and so the world becomes increasingly uncertain. Uncertainty brings unlimited possibilities, as well as the anxiety of vanishing conventions. I’m fascinated by the superimposition of many different ways of seeing born amidst these changes. The uncertainty of our reality seems coextensive with our visual experience; this is a result of the necessities of globalization for repetition and upheaval. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I want to express this feeling in my work.

When it comes to visual presentation, I try to avoid using images (even though a painting must ultimately become a fixed image); I prefer to draw the painting, bit by bit. My body’s reactions to the composition, color, and brushstroke are impossible to counterfeit.

Much of my oil painting technique comes from working with paper and water-based paints (in art school, our teacher taught us to slowly minimize the use of diluted oils, while increasing the use of color oils and varnish). In April, Lévy Gorvy invited a materials specialist to a Zoom talk; the specialist suggested that after finishing layering paint on my canvases, I could use less turpentine. I thought about it for a long time, then implemented some of these suggestions. I continued to add diluted oils to areas with lighter color, because I wanted to achieve the effect of painting on paper or the surface of a wall. This way, my paintings would be more subtle, deeper, and involuted. More importantly, it allowed me to increase the density of my compositions, avoiding an overly glossy, transparent effect, thereby satisfying one of my desires for texture.

David Hockney. Twenty-Five Big Trees Between Bridlington School and Morrison’s Supermarket on Bessingby Road, in the Semi-Egyptian Style, 2009. See: M. Gayford, Y. Wang tr., A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2013) pp. 110–11.

Edward Ruscha. Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966. Artist’s book, 7 1/8 × 5 5/8 x 7/16 inches (18.1 x 14.3 cm). See: T. Crow, W. Jiang, and T. Deng tr., The Rise of the Sixties: American and European Art in the Era of Dissent (Nanjing: Jiangsu Phoenix Art Publishing House, 2020). Image: The Getty Research Institute, 86-B19486.

Nymph of the Luo River. c. 345–406 CE. Handscroll, ink, and color on silk, 10 11/16 x 225 1/2 inches (27.1 x 572.8 cm). Palace Museum, Beijing. A copy of the original painting by Gu Kaizhi from the Southern Song Dynasty.

By Tu Hongtao

-

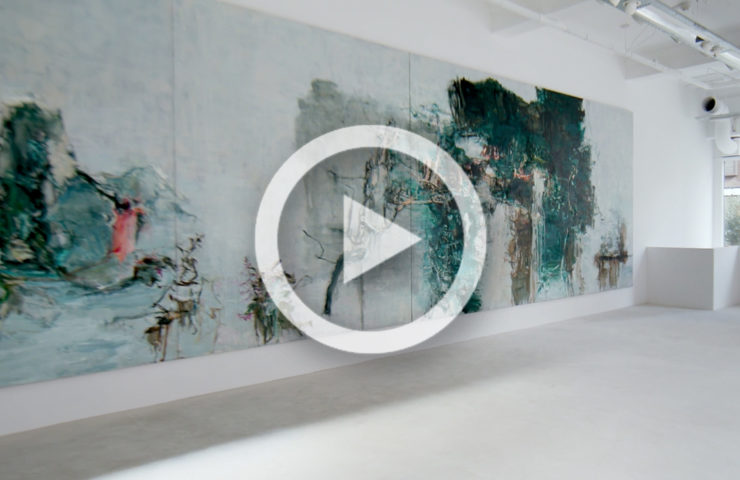

Installation Views, 40 Albemarle Street

-

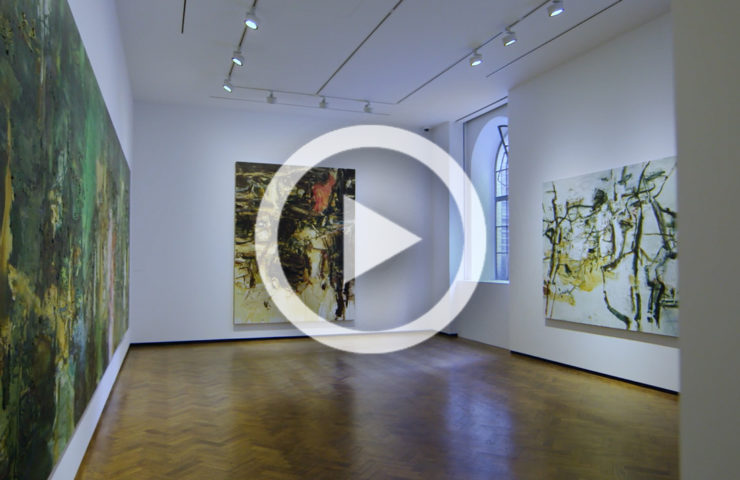

Installation Views, 22 Old Bond Street

-

Artist Statement | Tu Hongtao on the Exhibition Title

-

Green Mountains Shall See Me Like This

2019

-

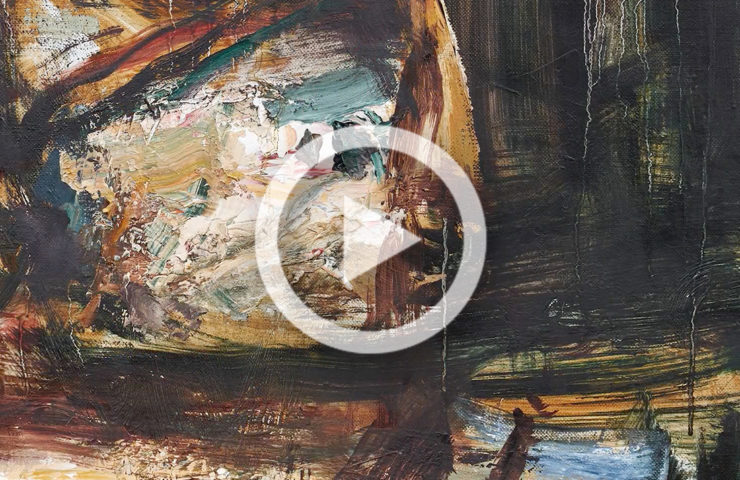

Film | Green Mountains Shall See Me Like This, 2019

-

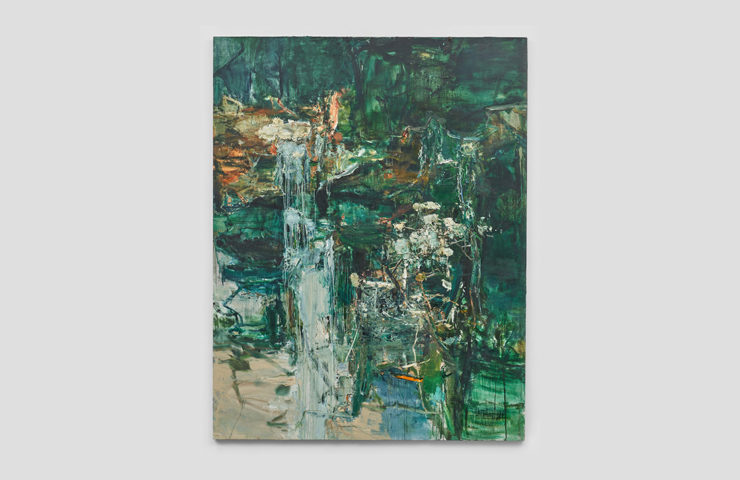

Falling Leaves Rustling Down

2019–20

-

Film | Falling Leaves Rustling Down, 2019–20

-

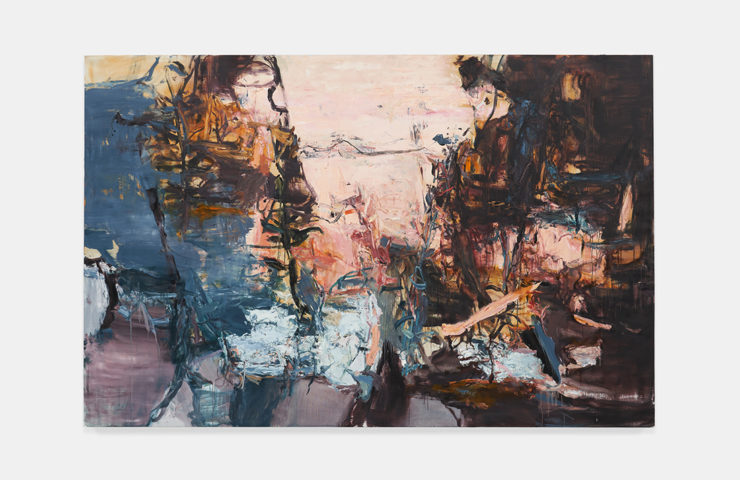

A City of Sadness

2019–20

-

Flowers in the Mountain Shades

2019–20

-

Stream-Fallen Leaves-Deep Valley

2019–20

-

Spring River in the Flower Moon Night

2019–20

-

Artist Statement | Thoughts on My London Exhibition

-

Summer River Virid Water

2020

-

Swinging Time

2019–20

-

Thoughts in Remote Mountains

2019–20

-

Image of Strange Stones

2020

-

Film | 40 Albemarle Street

-

Film | 22 Old Bond Street