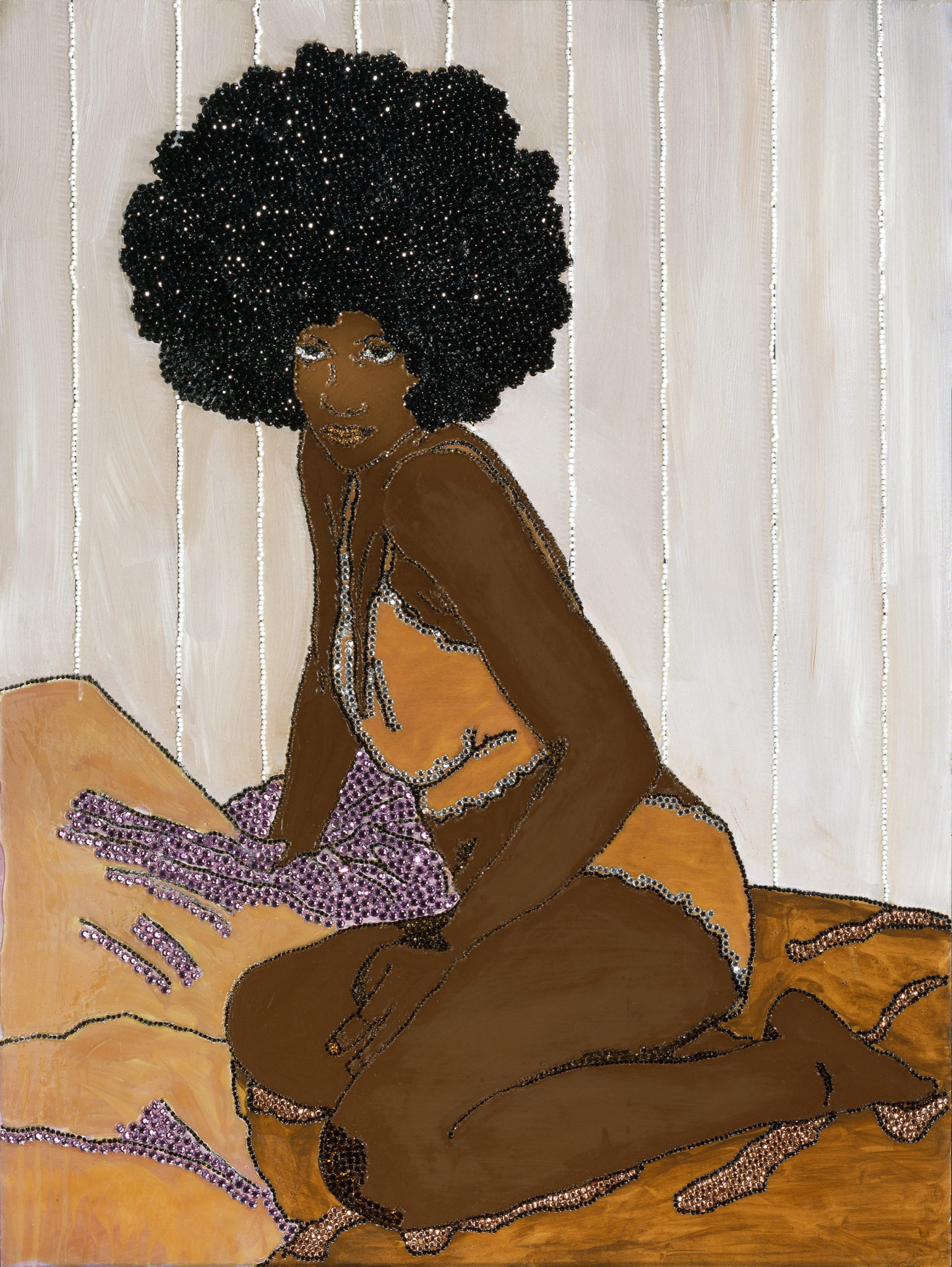

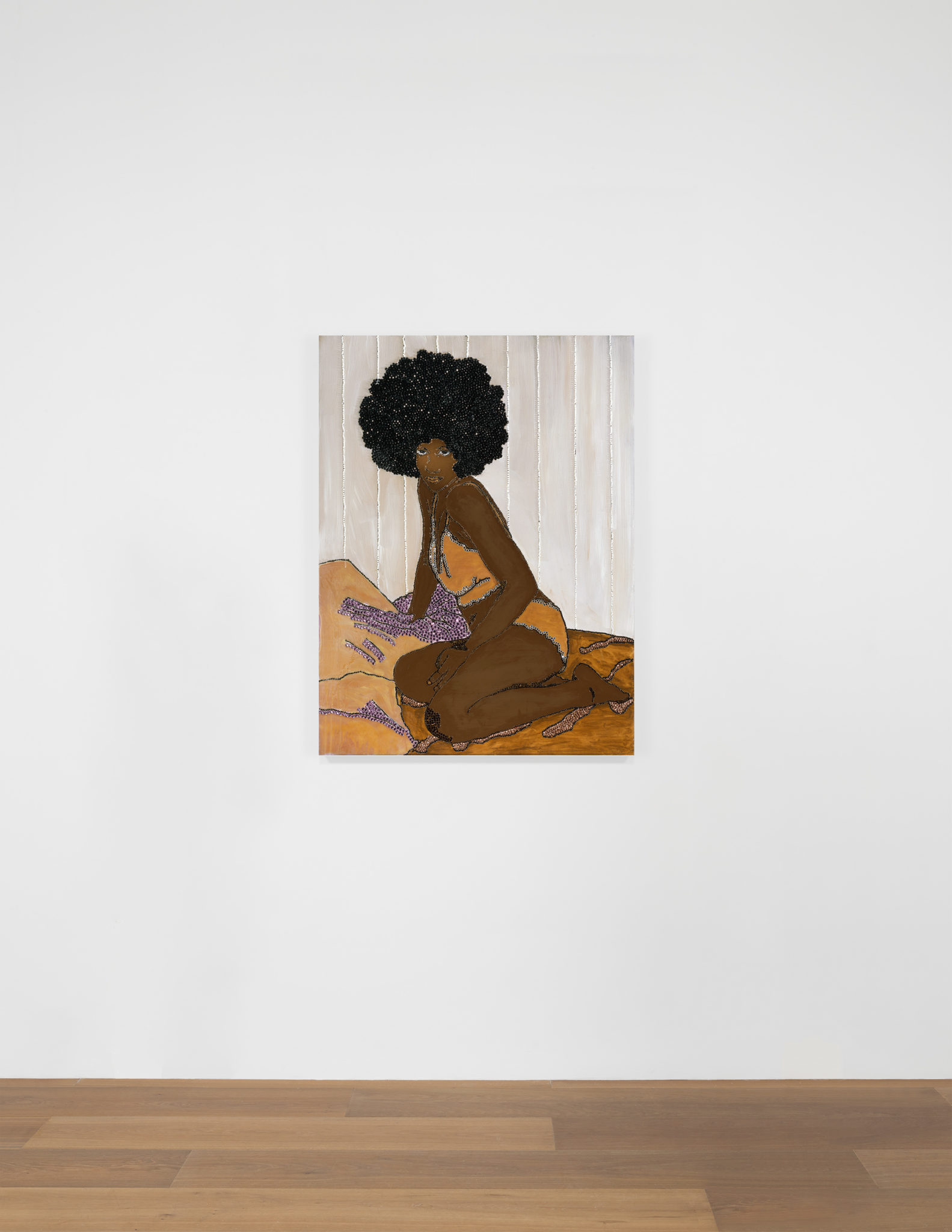

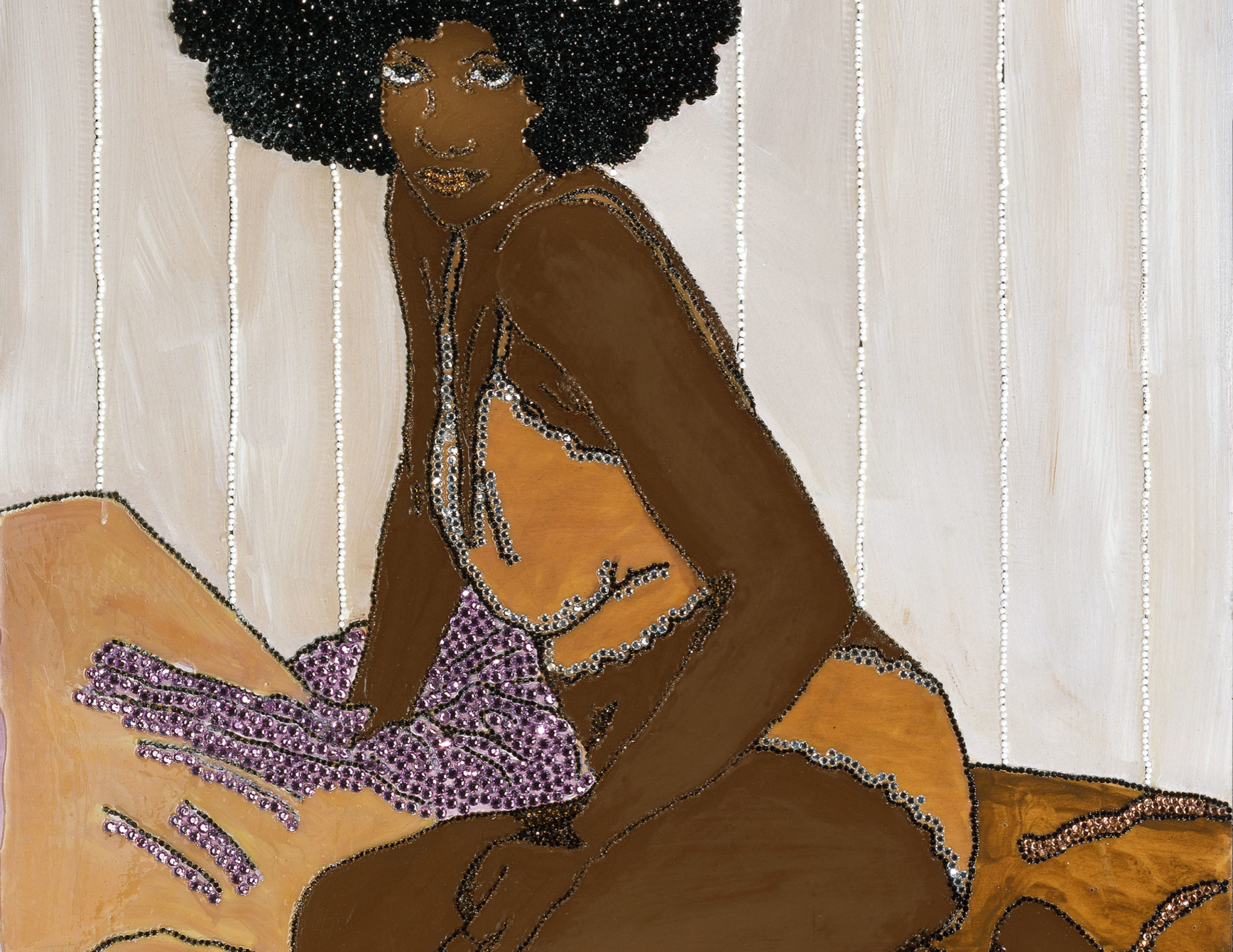

Mickelane Thomas

Sugar Baby, 2004

Acrylic and rhinestones on panel

48 x 36 inches (121.9 x 91.4 cm)

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I wanted to celebrate black femininity, and that sexuality, in a different way, by claiming the space that seemed to be voided for a while… and started thinking about art history and looking at iconic paintings… I thought, why isn’t the image of a black woman held up to that same light?

—Mickalene Thomas

Sugar Baby (2004) asserts the unabashed confidence inherent to Mickalene Thomas’s investigations of black female beauty and its place in art history. Thomas draws inspiration from Western masters, particularly the men who dominated the era of early modernism such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Edouard Manet, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. She models her figures on the classic poses associated with these artists as a way to reclaim agency for black women, who have traditionally been subjugated as slaves, maids, or erotic objects. In the present work, Thomas’s signature rhinestones allude to an earlier interest in pointillism’s division of space, while her subject establishes direct eye contact with the viewer in the same way Manet’s nude looks amusedly out at her shocked audience in Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1862–63).

Enhanced by the scintillating rhinestones, Sugar Baby emanates the 1970s disco glamour of Thomas’s upbringing. This was a time of immense social and political conflict, change, and transformation—the civil rights movement, the Black is Beautiful movement, and the second wave of feminism—during which many women, particularly African Americans, rejected and redefined traditional standards of beauty. The retro-inspired colors and textures of the interior and clothing recall the wood-paneled living room of her childhood where, Thomas has recounted, “the women of my family would come together for intense dialogues.” Here is a setting in which she recognized qualities of strength, liberation, and intellect in black women—most notably in her mother. As a result, Thomas’s artistic output remains deeply personal, while calling for a wider reinterpretation of canonical Western art.

-

Andy Warhol

Ladies and Gentlemen (Wilhelmina Ross), 1975

-

Eduardo Chillida

Gure aitaren etxea, 1984

-

Carol Rama

Presagi di Birnam (Omens of Birnam), 1994

-

Mario Schifano

Untitled, 1975

-

Michelangelo Pistoletto

Rottura dello specchio–azione 2, 2017

-

Lygia Clark

Bicho em Si – Pq, 1966

-

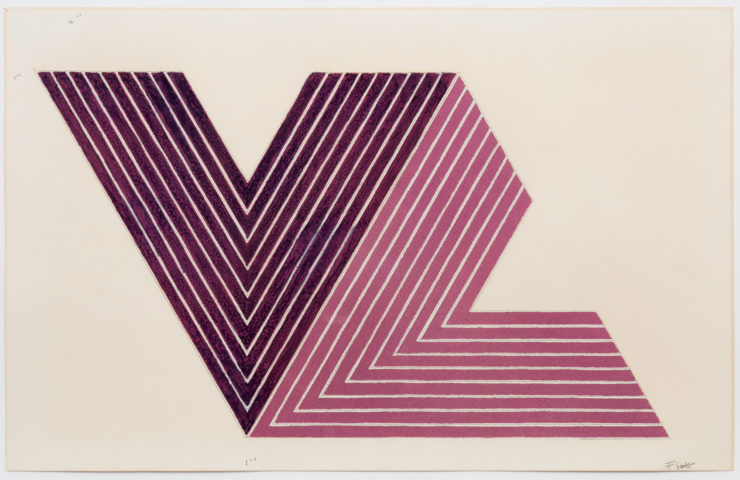

Frank Stella

Untitled, 1969

-

Enrico Castellani

Superficie argento, 2006

-

Jana Euler

Dirty Gossip Rain, 2013

-

Carol Rama

Bricolage, 1963

-

Mickelane Thomas

Sugar Baby, 2004